Fat loss can be frustrating at times. You lose fat more slowly than you think you should, your progress stalls completely, it feels like your metabolism is broken, you do cardio but it doesn’t seem to help, or life gets in the way.

Some things that interfere with your fat loss efforts are out of your control. But in many cases, the frustration is self-inflicted because you don’t yet understand or are not yet willing to admit the truth about how fat loss – and human bodies – work.

Sometimes the facts are unpleasant. There are truths you may not want to hear, but they’re things you need to hear. As Carl Sagan once said, “Better the hard truth than a comforting fantasy.” When you learn the truth about fat loss, and accept it, you still might not be happy about it, but that’s when real change starts to happen.

In this in-depth Burn the Fat Blog post, you’ll learn 10 of the most inconvenient fat loss truths. If you understand, accept, and respond to them the right way, you will break through any past barriers and forge on to the lean body you want.

1. Too much healthy food can lead to weight gain

Fat loss happens when you achieve a calorie deficit. Yet not all diets ask you to count calories. Some diets are based on the premise that all you have to do to lose weight is to eat certain foods and avoid others.

Guidelines urging you to eat unprocessed foods and avoid processed foods are well-intentioned on two levels. One is because less processed foods make you healthier. The other is because processed foods are usually more calorie-dense and hyper-palatable, so focusing on eating healthier foods usually does help you control calories, and that helps with fat loss.

But there are always many frustrated dieters screaming, “I’m eating healthy, but not losing any weight!” Why does this happen? Because you’re eating too much healthy food!

Healthy foods are not calorie-free. Too much of anything, even healthy foods, will get stored as fat. You don’t get an unlimited all you can eat pass. Ever. But for some reason this fact doesn’t register in the brains of many health food eaters.

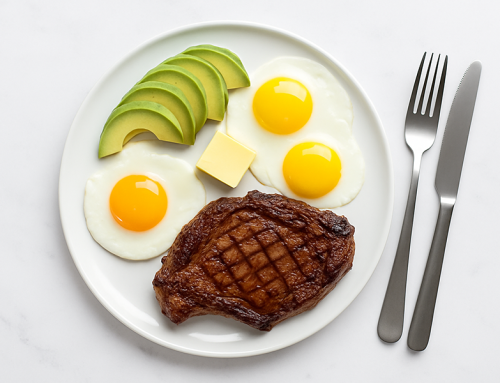

Many foods with a reputation for being healthy, especially fats like avocado, natural peanut butter and olive oil, are calorie dense and easily overeaten into surplus levels. Making it worse, the popularity of keto diets has normalized eating more fat, including things like coconut oil, which is perceived by some people as healthy but adds hundreds of extra calories to their diets.

The truth is, eating healthy foods doesn’t get you lean. Eating healthy foods gets you healthy. A sustained calorie deficit gets you lean.

2. You can lose weight and stay lean on a junk food diet

Admit it. It drives you insane when you see a friend or family member “eat anything they want” and still stay slim. These are not mythological creatures – you will meet people that you personally witness eating cookies, ice cream, chocolate, pizza, and just about anything else they like, and they don’t carry an ounce of excess body fat, nor seem to gain any. It doesn’t seem fair.

Your knee jerk reaction is to assume they’re genetically gifted with a fast metabolism. What you don’t see or add up is how their total calorie intake for the whole day and whole week equals their maintenance level. That’s why they don’t gain weight. It’s not their metabolism, it’s math. If you’re not in a surplus, you don’t gain weight.

Proof of this concept can be found in the numerous diet experiments like the one Mark Haub did. Remember him? He’s the Kansas State professor who made headlines by losing weight on a Twinkie diet. How? He tracked his calories and made sure he had a deficit. Stunts like this have been documented by people who ate nothing but McDonalds as well. Twinkies don’t turn into fat. McDonalds doesn’t turn into fat. Excess calories turn to fat.

Do I recommend eating a lot of junk and fast food in a deficit because you can get away with doing that and still lose weight? Of course not. We aim to eat healthy unprocessed foods 80 or 90 percent of the time so we can be lean and healthy, not just lean. While health and fat loss overlap, they are two separate goals. If you want to achieve both, then you’d better get calorie quantity and calorie quality right, not one or the other.

3. You don’t have a slow metabolism

Yes, your metabolism slows down after dieting and losing weight. The technical name is adaptive thermogenesis, or simply metabolic adaptation. This is the normal response that everyone has to dieting and weight loss.

Is it enough to slow down progress slightly and frustrate you because your rate of fat loss doesn’t match what you’d predict on paper? Yes. Does it stop or prevent weight loss? No. Metabolic adaptation is a real thing, but having a slow metabolism does not hold up as a reason for not losing weight.

A study done at St Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital in New York was especially enlightening because it involved subjects who reported a history of “diet resistance.” They claimed they ate only 1200 calories per day but weren’t losing weight. They’d been stuck at the same weight for at least six months. They blamed their lack of results on slow metabolism, genetics, or thyroid problems.

First, before sharing what this study found, let’s clear something up: The belief that obese people have a slower metabolism is a myth. In fact, the opposite is true. Men and women with a large body mass burn more calories because resting metabolic rate is directly linked to total body mass.

Big heavy people burn more calories than smaller lighter people. This is why obese people can lose so much more weight each week than smaller people – it’s much easier to create a large calorie deficit. Plus, the calorie cost of moving around a large body is greater than moving a light body.

Even with this in mind, many overweight people assume they’re unique and really are cursed with a genetically inherited slow metabolism.

So now, back to this classic study, which was published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). The researchers wanted to settle the issue by doing an experiment where calories eaten and calories burned were measured under tightly controlled conditions.

The subjects were given a test for resting metabolic rate, the thermic effect of food, and the thermic response to exercise. They also used doubly labeled water (an accurate method to measure energy expenditure under free-living conditions). Body composition was tested with underwater weighing.

The results were a surprise to the subjects, but confirmed the hypothesis of the researchers:

The resting metabolic rate, the thermic effect of food, oxygen consumption in response to exercise and total energy expenditure did not differ significantly between the test groups. None of these subjects who swore up and down they were “diet resistant” had a low resting metabolic rate or a low total energy expenditure.

Why weren’t they losing weight? That’s the next inconvenient truth.

4. You eat more calories than you think

Almost everyone eats more than they think, especially when not tracking food intake. Why? Because almost all of us are bad at estimating how many calories are in our food. It’s not easy to eyeball a food portion and correctly guess the calories (darn near impossible in restaurants).

Granted, it’s possible for some people to manage food portions and control their weight if they master instinctive eating and mindfulness skills. But when nothing else is working, the only sure-fire solution to underestimating calorie intake is to weigh and measure food and track the calories and macros.

In the same NEJM study which found that so-called “diet resistant” people did not have slow metabolisms, they also discovered the real cause for the lack of weight loss: The subjects underestimated their calorie intake by 47%! That’s not a minor mistake – that’s a massive “make you or break you” kind of mistake!

The researchers said, “The failure of some obese subjects to lose weight while eating a diet they report as low in calories is due to an energy intake substantially higher than reported, not to an abnormality in thermogenesis.”

To be fair, we should acknowledge that there are some clinical explanations for short term diet resistance. For example, undiagnosed and untreated thyroid disease could cause difficulty with losing weight. Certain medications can stimulate appetite or decrease calorie burning. And there are a handful of medical conditions that can hinder fat loss efforts.

In this study however, people with these issues were excluded, so these exceptions were ruled out. Lack of weight loss wasn’t caused by slow metabolism, thyroid problems, or medication side effects, it was caused by eating too much food.

It’s important to know that we’re not saying frustrated dieters are dishonest about how much they eat. They’re simply not aware that they eat so much because it’s so hard to guess the calories in meals, and so easy to lose track over time.

5. You think you burn more calories than you do

Equally alarming as the underestimation of calories eaten is the overestimation of calories burned. In the NEJM study, the subjects not only under-estimated their food intake by 47%, they over-estimated how many calories they burned by 51%! Think for a minute about the impact of both put together.

In a different study, researchers from York University in Toronto had a group of test subjects exercise on a treadmill for 25 minutes at either a moderate or intense level. After the exercise, they were asked to estimate the number of calories they burned and create a meal containing that many calories.

This study was also cleverly designed in the way they used different groups, including some individuals who were not trying to lose weight. There were four types of participants in the study:

1. Normal weight

2. Overweight

3. Trying to lose weight

4. Not trying to lose weight

Every subject did a poor job trying to estimate calories burned, with one group (overweight, not trying to lose weight), doing a terrible job: They overestimated their calories burned by 72%!

The subjects who were trying to lose weight did better, but still failed to accurately estimate their calories burned and eaten. In all the participants from all four groups, there was a range of calories burned estimation error between 280 and 702 calories per day.

6. You probably eat back some or all of the calories you burn

“Exercise is not effective for weight loss.”

“Cardio is a waste of time.”

“Aerobics makes you fat.”

“Some people are cardio-resistant.”

“You adapt to cardio so eventually it stops working.”

What do these five statements, each one made by prominent diet book authors or personal trainers, have in common? Aside from the fact that they’re wrong, they’re all alike because they miss or ignore the real reason why cardio doesn’t increase fat loss (“doesn’t work”) for some people…

But first, why would people say these things? Well, it’s not my intention to belittle anyone for saying that exercise doesn’t seem to help them lose weight. In fact, studies have confirmed that a fixed amount of aerobic exercise doesn’t produce the same amount of weight loss in different individuals.

The problem is in the way some people try to explain the reason they’re not losing weight.

It’s not because exercise doesn’t work for fat loss (it does, and reliably so).

It’s not because calories don’t count (they do).

It’s not because they are exercise-resistant (they’re not).

The biggest reason different people get different results from the same cardio is because they all may do the exercise consistently, but diet compliance varies from person to person.

Many people start doing cardio or increase their cardio, but at the same time, usually unconsciously, they fail to stay on their diet plan. They exercise more, but also eat more, which cancels out the fat loss benefit of the exercise (increasing a deficit). Researchers call these people “compensators.”

Some experts claim that people eat more because cardio increases their appetite. This may happen in some people with some types of cardio, but exercise does not always increase appetite – that’s a myth. In some cases, it even suppresses appetite.

Even if your appetite does go up after doing cardio, if you eat more in response to that, it doesn’t mean the exercise doesn’t work, it means you made a diet mistake (compensation). Contrary to popular wisdom from intuitive eating, if your goal is fat loss, you should not always “eat when you’re hungry.” Harsh truth: You have a deficit you must comply with, and sometimes you have to feel hungry and not eat.

This mistake is also common because it’s a mental response as much as physical. In psychology there’s a concept known as moral licensing. It means there’s a human tendency for doing something good for yourself, then seeing that as permission to do something bad. Exercising and then rewarding yourself with junk food is the classic example.

Many people also go through a conscious rationalization process where they figure if they exercised, they “earned” more food and can get away with eating more because they worked out. This problem is compounded because of how most people think they burn more calories than they do.

Even worse, people who use fitness trackers to monitor how many calories they burn and then adjust their food intake based on calories burned are often unknowingly sabotaging themselves.

7. Deciding how much to eat based on how many calories a fitness tracker says you burned can make you fatter

Tracking the calories you burn from your workouts could sabotage your fat loss? What? Aren’t you supposed to do that? Isn’t it a good idea to use fitness trackers to monitor your calorie burn? Don’t you want to know how many calories your 45 minutes on the treadmill burned off?

Obviously, it matters how many calories you burn each day – that’s part of the energy balance equation. Being more active is great for fat loss and fat loss maintenance.

But if you try to use information about calories burned from each workout to make adjustments to how much you eat each day, you’re in grave danger of making a monumental fat loss mistake.

Most people want to know how many calories each workout burns because they think they can reconcile calories in versus calories out, adjust their food intake up or down, and try to ensure a calorie deficit every day.

Most people also figure if they burn more on one day, they’ll eat more, and if they burn less on another day they’ll eat less. Often, they rationalize that if an epic workout burns a lot more than usual, they have plenty of room to add in a treat meal or an extra tasty snack.

This all seems perfectly logical, and in some ways, it is. If you burn 3000 calories a day, you can eat a lot more than someone who only burns 2000 calories per day and still lose weight.

Yet most people are surprised or shocked when I tell them you don’t need to know how many calories each individual workout or activity burns.

Here’s why: Your exercise calories burned were already counted.

When you initially set up your nutrition plan, the first thing you do is use a calorie calculator formula to estimate your basal metabolic rate (BMR). That’s how many calories you burn just to cover basic body functions.

The second thing you do is estimate your activity level. This includes formal workouts as well as work, walking and all other daily activity. This is where your average daily exercise calories burned are already counted, in advance.

When you multiply your BMR by your activity factor, you then have your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) also known as your maintenance level. That’s the grand total of all the calories you burn in a day.

You can do these calculations by using equations such as the Katch-McArdle or the Harris-Benedict calorie formula, which are featured in the Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle book as well as available online including at our Burn the Fat Inner Circle.

If you want to lose fat, the third step for meal plan set up is you simply drop calories a little below that, maybe 20 to 30% under maintenance. That deficit is where your weight loss comes from.

Here’s the key point: Since you already counted all your exercise calories burned in those initial calculations, counting workout calories again would be not only be redundant, if you ate more, you’d be eating away your deficit.

Suppose you look at the treadmill readout and it says you burned 500 calories. It’s tempting, almost a natural reaction, to think you should add that on top of your daily burn and eat 500 more calories. That’s not how you manage calories for fat loss – that’s a diet mistake that wipes out your calorie deficit.

In fact, how many calories individual workouts burn should not even be your main focus. Instead, focus on the number of calories you’re supposed to eat, which you calculated in advance. Follow your baseline meal plan all week long.

Measure your results every week (weight, body composition, measurements, visual assessment) and if you achieved the fat loss you wanted, don’t change a thing. If your fat loss stalled, then decrease your calories for the next week. Alternately, increase your cardio duration or frequency or intensity.

I love fitbits and fitness trackers as a motivational tool to remind you to move more, or to record your running stats and so on. But I never recommend using a tracker for adjusting your food intake day to day.

Eating back calories burned = diet sabotage

8. One weekend of overeating can cancel out a whole week of dieting and training

Most people believe the cliché, “You can’t out-train a lousy diet” is more or less true. At the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, a study was designed to find out whether a “lousy diet” on weekends specifically, was causing weight loss failure.

Prior to this study, the best evidence for weekend eating causing fat loss plateaus or weight gain, came from the National Weight control Registry (NWCR). NWCR research had found an association between lower weekday to weekend diet consistency with weight loss relapse. People who maintained the same eating patterns on weekends as weekdays were more likely to maintain their weight during the subsequent year.

The newer study was a randomized controlled trial with a large sample size, and it ran for a whole year. It measured compliance to diet and exercise during the week as compared to the weekend, as well as changes in body weight during the week as compared to the weekend.

Over the entire 52 weeks, what they discovered was that both test groups – a calorie restricted group and an exercise group – successfully adhered to their calorie deficit on the weekdays. On the weekends, however, calorie restricted participants stopped losing weight and exercise participants actually gained weight.

The study was the first controlled trial to confirm what the NWCR had reported observationally and what we always suspected: weight gain does happen on the weekends more than the weekdays and it’s because of increased calorie intake on the weekends. Things go awry because most people have different eating schedules, patterns or habits on the weekends than on weekdays.

Calorie intake was highest on Saturdays – about 236 calories more than on weekdays, mostly from fatty foods. A couple hundred calories more on Saturday doesn’t seem like much, and of course it’s possible to eat more on some days than others and still have a weekly deficit.

But the excess calories most people eat on weekends are not a part of deliberate, controlled refeeds, built into a weekly plan to maintain an overall deficit. The weekend excess most people eat is overlooked and adds up over time.

Just this barely noticeable increase in weekend food intake could cause a weight gain of nearly 9 pounds if you didn’t catch it and let it go on unchecked all year long. And of course, some people indulge even more than others from Friday night through Sunday, so the fat gain could be even higher.

There’s been a lot of research done on how diet and activity changes during the holidays and over the changing seasons. But there’s a big difference between holiday indulgence and weekend indulgence. A big splurge on your birthday, Thanksgiving, and Christmas? Okay, that’s only a few times a year. Weekends come around 52 times a year.

9. Women can’t eat like men – if they try, they won’t lose fat

Many women think they have trouble with fat loss because of hormones. But the biggest obstacle is not hormonal, it’s one little relativity factor that almost all women overlook: Women are usually smaller and lighter than men, yet their mistake is setting their calorie intake, their goals, and expectations like men (or larger women).

When you have a smaller body, you need fewer calories. When you have lower calorie needs, your relative deficit (20%, 30% etc) gives you a smaller absolute deficit. Therefore, you lose fat more slowly than someone larger who can create a bigger deficit more easily.

Me: I’m male, 5’ 8”, 192 pounds in “off-season” condition, and very active:

Daily maintenance level: 3300 calories a day

20% deficit: 660 calories

Optimal intake for fat loss: 2640 calories a day

On paper predicted fat loss: 1.3 lbs of weight loss per week

At 2640 calories per day, I’d drop fat rather painlessly. If I bumped up my calorie burn or decreased my intake by another 340 a day, that would be enough to give me 2 pounds per week of weight loss. Either way, that’s hardly starvation.

For women, especially lighter, shorter women, the math equation is very different.

At age 40 and only 5 feet tall and 115 pounds, a woman’s numbers would look like this:

Daily maintenance level: 1930 calories (even when moderately active).

20% deficit: 386 calories

Optimal intake for fat loss: 1544 calories a day

On paper predicted fat loss: only 8/10th of a pound of fat loss/week.

If you took a more aggressive calorie deficit of 30%, that’s a 579-calorie deficit which would now drop the calorie intake to 1351 calories/day.

That’s pretty low in calories, but it’s still fairly small calorie deficit. In fact, I would get to eat twice as many calories (2600 vs 1300 per day) and I’d still get almost twice the weekly rate of fat loss!

I know it’s not fair, but it doesn’t mean women can’t get as lean as they want to be. It means that on average, women will drop fat a lot slower than men. It also means petite women with small bodies will always lose fat very slowly.

The only answer is patience and meticulous tracking, because even small calorie errors turn into big setbacks. One extra muffin, cookie or serving of peanut butter, and POOF, just like that, the calorie deficit is gone.

10. You can’t burn much body fat in a 4-minute workout no matter how intense it is.

A claim that lots of people take at face value without thinking it through is that you can burn more fat in a workout just minutes long (4 minutes, 7 minutes, etc) than you can with a long steady state workout, say 40 minutes, if the short workout is super high in intensity.

The mistake is confusing pounds of fat tissue being burned off your body week by week with calories burned per minute in a single workout.

Suppose you did a high-intensity workout with a huge calorie burn of around 20 calories per minute. That would mean you burned 80 calories in 4 minutes. Is that a lot of calories burned in 4 minutes? Absolutely! Are there cardio health benefits gained in only 4 minutes with an intense effort? For sure. Is it enough total calories burned to produce much body fat loss? No way.

The 4-minute workout craze came from the Tabata protocol, which is a type of HIIT where you do 20 second bursts of intense work followed by 10 seconds of rest (30 seconds per round) and you repeat that 8 times (a total of 4 minutes). It’s a legitimate training protocol and a time-efficient way to achieve fitness. But sorry, one round of that won’t put a dent in your body fat stores. Even two or three rounds – that’s better, but still, don’t expect much fat loss.

When you get up to 20 to 30 minute high-intensity interval workouts, or 40 to 45 minute moderate intensity steady cardio, then you’ll start to see the body fat fall off you. (If you don’t mess up your diet, that is). 4 minutes, or 7 minutes or 10 minutes – any of these minimalist workouts we see advertised all over the place simply aren’t going to cut it.

Consider first that how many calories you burn depends on your body size. Remember what we said earlier about bigger people burning more calories? That’s true during exercise as well as at rest (basal metabolism). Unless you’re a big, tall man, you probably don’t burn as many calories as you think from training.

Second, consider that the number of calories you burn doing Tabatas or other types of HIIT depends on the exercise you choose. If you do something easy like bodyweight-only squats, will you burn 20 calories per minute? No way. Will you achieve a huge afterburn? No. The way Tabata was done in the original research was all-out bicycle sprints to the point of vomitous exhaustion.

That brings up a third point. Many people can’t handle sprint-level intensity. They’re physically incapable, it makes them nauseous, or they simply hate it. The best workout is a lot like the best diet – it’s the one you like, can tolerate, and stick to consistently.

HIIT advocates often insist that the only cardio worth doing is intense. The truth is, studies show that you can burn just as much body fat with low or moderate intensity cardio as you can with high intensity cardio – it simply takes longer. Intense cardio is more efficient, but not necessarily more effective.

So you see, when it comes to fat loss, there’s no real shortcut, either way. If you don’t have much time, you have to work really hard. If you don’t want to work really hard, you have to work longer.

Last but not least, remember that fat loss from exercise is a function of total calorie burn. Total calorie burn is a function of frequency times duration times intensity, not intensity alone. You can increase your fat loss by turning up the dial on any one of those variables. You can also do it without ever worrying about the number of calories you burn, simply adjust your training volume based on your results each week.

More importantly, adjust your diet. As you’ve discovered after reading this list of inconvenient truths, focusing on calories burned at each workout may not be such a great idea.

More importantly, adjust your diet. As you’ve discovered after reading this list of inconvenient truths, focusing on calories burned at each workout may not be such a great idea.

Keep up your training – weight training and cardio training. But the real key to fat loss success is to control your diet by focusing on the number of calories you eat every day and making sure you have a calorie deficit.

And that’s the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

Tom Venuto, author of:

Burn The Fat Feed The Muscle

IS FAT LOSS YOUR #1 GOAL? Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle is the classic “bible of fat loss,” based on the tested, proven methods of bodybuilders and fitness models. The latest edition is now available not only in hardcover, but also in audiobook here: https://amzn.to/2pCG7lX

IS BUILDING MUSCLE IN LESS TIME YOUR #1 GOAL? IF so, The New Body (TNB) TURBO is the program for you: Ultra-time efficient “superset” training proven by science to build muscle in 50% of the time. To learn more CLICK HERE

Scientific References

Lichtman, S., Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. New England Journal of Medicine. 327: 1893-1898. 1992

Brown RE, et al. Calorie Estimation in Adults Differing in Body Weight Class and Weight Loss Status. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2015.

Jakicic JM, et al, Effect of Wearable Technology Combined With a Lifestyle Intervention on Long-term Weight Loss: The IDEA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 316(11), 1161-1171. University of Pittsburgh. 2016

Racette, Susan, et al., Influence of Weekend Lifestyle Patterns on Body Weight, Obesity, 16:8, pp 1826-1830, 2008.

Blundell JE, cross talk between physical activity and appetite control: does physical activity stimulate appetite? Proc Nutr Soc, 62, 651-661. 2003

Donahoo WT, Variability in energy expenditure and its components. Curr Op Clin Nutr Metab. 7: 599-605. 2004.

King NA, et al, Individual variability following 12 weeks of supervised exercise: Identification and characterization of compensation for exercise-induced weight loss. Int J Obes, 32, 177-184, 2008.

King NA, effects of exercise on appetite control: Implications for energy balance. Med Sci Sport Exer, 29(8): 1076-1089. 1997

King, NA, The relationship between physical activity and food intake. 57: 77-84. 1998.

Lluch A, Exercise enhances palatability of food, but does not increase food consumption, in lean restrained females. Int J Obes, 21: supp a129.

Melzer K., effects of physical activity on food intake. Clin Nutr, 24: 885-895. 2005

Reily N et al, Development of a scale to measure reasons for eating less healthily after exercise: the compensatory unhealthy eating scale, Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 8:1, 110-131, 2020

Slentz CA. Effects of the amount of exercise on body weight, body composition, and measures of central obesity. Arch Intern Med. 164: 31-39. 2004

West, J et al, “I deserve a treat”: Exercise motivation as a predictor of post-exercise dietary licensing beliefs and implicit associations toward unhealthy snacks, Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 2017

Tom Venuto is a natural bodybuilding and fat loss coach. He is also a recipe creator specializing in fat-burning, muscle-building cooking. Tom is a former competitive bodybuilder and is today a full-time fitness writer, blogger, and author. His book, Burn The Fat, Feed The Muscle is a classic and an international bestseller, first as an ebook and now as a hardcover and audiobook. Tom’s book about emotional eating and long-term weight maintenance, The Body Fat Solution, was an Oprah Magazine and Men’s Fitness Magazine pick. Tom is also the founder and CEO of Burn The Fat Inner Circle – a fitness support community with over 51,000 members worldwide since 2006. Click here for membership details

I really appreciate you no BS approach to fitness Tom. I have used your book as a reference for years I recommend it to everyone. Thanks

Jason Coyne

hi Jason – thanks for your post. The Burn the Fat book is always a great reference because the fundamentals never change. Thank you for recommending it to others. Reach out any time if there’s ever any way I can help

40 minute workouts sounds like a good idea. But can you split this into two twenty minute sessions and still get the same benefit?

Yes. 100%. 40 minutes in one go or 20 minutes twice will provide the same benefit

Thanks Tom. Very grateful for your advice and had two great sessions yesterday.