Have you suffered metabolic damage? Has your body gone into starvation mode? Are you experiencing metabolic adaptation to weight loss? If you’ve struggled with ongoing weight loss or weight regain, I’m going to suggest that the answers to those questions are no, no, and yes. I’ll explain why in this comprehensive post…

Ever tried to lose weight? If so, you know that progress doesn’t always come in a straight line. More often than not, you lose weight at first, but then your weight loss slows down. It gets harder over time. Weight loss also seems unpredictable. You keep following the same plan, but you might lose two pounds one week, only a pound another week and nothing at all some weeks. And at the end of course, the work is only beginning. Maintenance is the real challenge.

Why isn’t weight loss easier ? Why isn’t weight loss more linear? Why don’t your results seem to match the calorie math you did when you started? Why is weight regain so common?

There are many reasons. Some are psychological. Some are social. Environment is big one. In today’s modern society, we are bombarded with so much gastronomic temptation that weight loss experts call it an “obesogenic environment.” Not only that, most people are under a ton of stress and eat to soothe themselves.

But if your weight loss progress has slowed over time, there’s also a biological reason. When you diet, your body adapts in ways that make you burn less and want to eat more. Collectively, all of these mechanisms are called metabolic adaptations.

In a recent issue of The Journal of Strength And Conditioning Research, an excellent scientific paper about metabolic adaptation was written by Brandon Roberts and Mario Martinez-Gomez. Citing 211 different studies, the authors explained exactly what’s going on in your body when it adapts to weight loss. That includes many hormonal changes. They also asked the question, “Is there anything we can do about it?”

In this post, I’ll recap these findings. I’ll also add my own thoughts to help answer both questions: What is metabolic adaptation and can we fix it?

The bad news is you can’t stop metabolic adaptation to weight loss completely. When you cut calories and lose weight, certain changes happen in your body automatically. The good news is, there are ways to mitigate metabolic adaptation. More good news is that if you apply these strategies, you’re not doomed to fail or to regain weight.

What Metabolic Adaptation Is NOT

Before you check out the 7 strategies, it’s important to first understand the real science behind metabolic adaptation. If you buy into common myths about metabolic adaptation, that can lead to making bad decisions about nutrition and training. It could also lead to feeling frustrated or even giving up.

The biggest myth is the one about starvation mode. Some people believe that if they drop their calories too low, their metabolism will slow down so much, they’ll stop losing weight. When the weight loss stops, they say to themselves, “I must have gone into starvation mode.” The truth is, “starvation mode” is not even a scientifically recognized term.

Your metabolic rate does slow down after being in a calorie deficit and losing weight. That’s part of metabolic adaptation. But what really happens is you simply lose weight a little slower than you predicted on paper. The idea that you could stop losing weight because you’re eating too little is false. In fact, it’s absurd if you think about what happens to real victims of starvation.

Metabolic adaptation is also not “metabolic damage.” Usually, metabolic damage is said to be not only a major drop in metabolic rate, but also failing to return to normal for a long time, or ever. Like starvation mode, metabolic damage is not a scientific phrase. But even if you want to use the term, it’s arguable whether it happens except in extreme scenarios.

When contestants from the weight loss reality show The Biggest Loser were studied, researchers found that each participant had an unusually large drop in their metabolic rate. On average, their basal metabolic rate was 500 calories lower than what you’d predict based on their drop in bodyweight. But the most shocking part was that this suppressed metabolic rate appeared to persist as long as six years after the weight loss competition ended.

Couldn’t this be held up as proof that metabolic damage is real? Some people think so, but these results have been questioned due to methodology (measuring energy expenditure is tricky). Even if they’re accurate, we shouldn’t extrapolate these findings to others because you would never see a situation as extreme as the Biggest Loser in real life. These men and women were doing ridiculous amounts of exercise, (90 minutes of intense daily training and up to several hours per day in total), combined with an equally extreme 1200 calorie per day diet. They lost insane amounts of weight – an average of 128 pounds.

The fact is, while metabolic adaptation to weight loss has been well documented, under normal circumstances, the adaptive thermogenesis part of it is usually not a huge drop. Here’s what most follow-up studies have found: Even among physique athletes who do pretty extreme diets themselves – metabolism goes back to normal within a short time after you bring your calories back to maintenance and your weight is stable.

A recent study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition followed 171 women for 2 years after they lost 26.4 pounds (16% of their initial weight). Metabolic adaptation did occur, but was only 50 to 60 calories per day (3% to 4%) below predicted levels. In this group, 52% had regained the weight after 1 year and 83% after 2 years. Avoiding weight regain is always a challenge. However, the regain did not correlate to the metabolic adaptation. Also, the reduced metabolic rate was no longer detected after the women were weight stable.

The idea of “metabolic damage” meaning a huge drop on metabolic rate that lasts long after weight loss is stopped is not well supported, or at least seems the rare exception not the rule. In the more recent study, the subjects were on an 800-calorie per day diet, and yet even with a calorie deficit more severe than the Biggest Loser contestants, their metabolic rate was back to the predicted level in just over 4 weeks of weight stability.

“Starvation mode” and “metabolic damage” are terms many of us used nonchalantly in the past. We still hear them quite often throughout the weight loss world today. But because they are somewhat hyperbolic, fear-inducing and easily misunderstood, we’d be better off if we dispensed with them.

Metabolic adaptation on the other hand, is real. It’s a normal response. It happens to everyone. And it goes beyond a drop in BMR. It also includes changes in hormones that make you want to eat more and move less. That’s what we’re talking about here.

To Understand Metabolic Adaptation, Understand Energy Balance

Energy balance is another way of describing “calories in versus calories out.” There are three general levels:

1. Positive energy balance (calorie surplus): You’re eating more than you’re burning.

2. Negative energy balance (calorie deficit): You’re burning more than you’re eating.

3. Neutral energy balance (calorie maintenance level): You’re eating the same amount that you’re burning.

The most basic principle of energy balance is that if you want to lose fat, you have to be in a calorie deficit.

You get into a calorie deficit by adjusting your food intake or your activity level. When we say activity, that can include your planned workouts as well as incidental activity and walking around during the day (non-exercise activity).

Ideally, you do a little of both at the same time, but almost everyone agrees that the diet side of the energy balance equation is the highest priority. That’s because it’s so easy to out-eat any normal amount of exercise the average person might do.

Diet gurus are notorious for suggesting that weight loss happens because you eat only specific foods, avoid certain foods, cut out carbs, control hormones, eat only at certain times of the day, remove toxins and a long list of other reasons. They’re wrong. When a diet works, the reason it works is because it helps you get into a calorie deficit.

It’s always oversimplifying to say, “weight loss is only about calories.” Many factors influence how many calories you eat and how many you burn. You’ll see just how true that is when we talk about hormones. But weight loss is still an energy math equation.

Let’s assume you agree that these laws of energy balance are true. Why then, does weight loss still seem so difficult, even when you calculate your proper calorie target and do your best to track your intake? Why does it seem like the math equation isn’t working out?

Answer: The math equation changes! Energy balance is dynamic, not static.

When you lose body mass, your total daily energy expenditure goes down. The rule of thumb is: bigger people require more calories at rest. Smaller people require fewer calories at rest. Hauling around a bigger body means you burn more exercise calories too. And vice versa.

After you’ve lost a lot of weight, you’re a smaller person, right? That means you don’t need as many calories anymore. If you’re still trying to lose more weight eating the same amount as you did at the start of the diet, your weight loss will be slower.

With a smaller, lighter body, there’s a different calorie math equation. That means to keep weight loss coming at the same rate, you have two options. One is eating a bit less than what you were before. The other is increasing your activity to a level higher than it was before. Or you could use a combination of both.

When this concept clicks in your mind, you suddenly realize why so many people gain back weight they lost. It’s not easy to eat less than you were used to eating for years and move more than you were used to moving for years. That’s the sobering reality.

And we’re just getting started with explaining metabolic adaptation to weight loss! When you eat in a deficit and lose weight, that triggers a whole cascade of adaptations that make it harder to keep losing more weight.

One metabolic adaptation to weight loss that we already mentioned is the decrease in your resting metabolic rate. Known as adaptive thermogenesis, this is an additional decrease not accounted for by the drop in your body mass alone. It’s usually not a huge drop, but it could amount to 10% or even 15% in extreme cases. That alone is enough to explain why you don’t always lose weight at the speed you’d predict based on your initial calorie calculations.

Put these two adaptations together – a drop in your calorie requirement after weight loss and adaptive thermogenesis, and then your calorie math equation has changed even more significantly.

Metabolic adaptation doesn’t stop there either. Metabolic adaptation is not just burning less, it’s also the way your body adapts to “trick you” into eating more. When you restrict calories and lose weight, hunger hormones go up, satiety hormones go down, so you keep reaching for more food.

But wait, there’s even more!

When you’re in a deficit and you’re losing weight, your body also “tricks” you into moving less. Part of this is you’re simply tired and low on energy when you’re not eating as much, but it’s deeper than that. Your body detects falling fat stores and less energy coming in, so it automatically (like a thermostat) reduces your level of non exercise activity thermogenesis.

Translation: You move less without even thinking about it. Your step count drops and little activities ranging from housework to fidgeting are spontaneously reduced.

Now do you see why weight loss can be so hard, so non-linear, so unpredictable? When you’re dieting and you’re losing weight, your calorie deficit is being assaulted from both sides!

Metabolic adaptation means you’re burning less (lower BMR and lower activity), and you’re eating more (and may not even realize it). When the weight is not coming off, this is where a lot of folks say, “my metabolism is broken” or “I must be in starvation mode!” As you now understand, your metabolism does slow down. But in some cases the increase in appetite and the decrease in activity are the bigger problems.

What can you do to reduce metabolic adaptation to weight loss?

Once you understand the science behind why your body adapts and you’re aware of what’s happening in your body during weight loss, you can adjust your behavior to at least partially compensate for the sneaky stuff your body does when it’s calorie-deprived.

You can put safeguards in place to make sure you stay active – all day long, not just during scheduled workouts. You can become more mindful so you don’t snack outside your planned meal times or under-estimate your food portions.

There are also specific diet and exercise strategies you can use to mitigate adaptation. In the next section, I’ll tell you about the hormonal changes that happen during metabolic adaptation to weight loss. Then, I’ll list each one of the 7 strategies to reduce it as much as you can.

But first however, let me explain one more bit of important background info. Let’s look at why we have these adaptive mechanisms in the first place.

Why Do Our Metabolisms Adapt? (Evolutionary Origins)

If obesity is so unhealthy, and if we’re genetically wired for survival of the species, then you’d think our bodies would develop adaptations to make it harder to gain fat, not easier. In one sense, our bodies are wired this way. The human body has mechanisms to maintain body weight homeostasis.

Unfortunately, our environment today overrides our biology. With cars, trains, elevators, and all kinds of labor-saving devices, plus jobs that keep us on our butts all day long, we move a lot less than our ancestors did.

Being surrounded by ultra-processed, hyper-palatable, easily-accessible food pushes our energy balance even further in the wrong direction. So even if we really do have some kind of “fat thermostat” that should normally keep our weight stable, it’s not enough to overcome these influences in our modern world.

Evolution may have also wired us to more easily preserve body fat stores. “The thrifty gene hypothesis” is the idea that throughout history there were many periods of famine. During those times, humans who were more resistant to starvation would live to reproduce and pass on their genes. Through a process of natural selection, more and more humans would posses these starvation survival genes.

Surviving a food shortage would mean having a physiology inclined toward easily putting reserve fat away in storage during times when food was available. It would also mean having a physiology that makes us inclined to increase food-seeking behavior, and conserve energy during times when food was scarce.

From the evolutionary perspective, these kinds of adaptations would perpetuate the species by allowing people to make it through long periods of food scarcity. The problem is, if we do carry these genes today, they work against our weight control efforts. In our modern environment, where food is over-abundant, these adaptations lead to obesity and disease.

This hypothesis about how we’ve adapted genetically may be an over-simplistic explanation to a multi-factorial problem. However, it does give us an easy framework for understanding adaptations that clearly exist, for one reason or another.

A different way some obesity experts explain how body weight is regulated is with the set point theory. This suggests that your body has a weight regulating mechanism that helps hold your weight close to a certain point without your need to consciously manage it. This has been compared to a thermostat in your home, in fact, some people call the mechanism an “adipostat” or “lipostat.”

Suppose your weight starts creeping too far in the direction of depleting your energy stores (body fat). The mechanism will automatically turn on and activate body systems that nudge you back to that normal point of homeostasis where you have a “safe” amount of energy in reserve.

Some experts prefer to look at it as a “settling point” rather than a set point, because a set point implies that if you lose weight at all, you’re doomed to always drift back to your normal set point. The less fatalistic settling point theory suggests that while your body resists weight change, you can settle in at a lower or higher body weight and then the system resets.

Another idea is that there’s a dual intervention point control system. This model says that your body fat has a fairly wide range where your weight will drift up or down in response to your environment and behavior without being opposed by physiology. But if your weight reaches a certain point either too high or too low, then the physiological systems flip on full force to bring you back into the normal range.

Our understanding of these systems is still developing, but we do know that the general concept of your body weight being regulated or “defended” because of metabolic adaptations is accurate. It also seems clear that your body defends a whole lot better against weight loss than weight gain!

How Specifically, Does Your Body Adapt? Hormones Are A Big Part Of It

Energy balance – whether you’re in a calorie deficit or calorie surplus – is the undeniable explanation for whether you lose weight or gain weight, respectively.

But if you are in a calorie deficit, all kinds of hormonal changes take place that collectively conspire to close the gap between the calorie deficit you were trying to sustain and your actual level of energy balance. Summed up simply, your metabolism drops, you move less, and you eat more.

The bad news is, you have little control over most of these adaptions. The good news is, you do have control over your behavior. The more you learn about how these adaptations work, the more vigilant you can be and the more you can adjust your behavior to reduce the effects of metabolic adaptation to weight loss.

With all of this background out of the way, let’s now look at some of the hormonal adaptations that can happen when you’re dieting in a deficit and losing weight.

Hormonal Control Of Energy Balance

1. Leptin.

Leptin is a hormone released by your fat cells which sends signals to your brain about how much fat you have in storage. If your fat reserves are high, your leptin is higher. This send a signal that your body is well fed and has plenty of energy in reserve. But if your body fat levels get low, your leptin level drops. This sends a signal that you’re running short on energy reserves. When your brain gets that signal, it flips on those systems to “help” you restore your body fat: hunger hormones go up, fullness hormones go down, and metabolic rate goes down.

2. Thyroid.

Thyroid is well known as a hormone that regulates metabolic rate. When you lose weight and get leaner, thyroid levels drop. It doesn’t take an extreme amount of weight loss to trigger this. In some studies, people who lost lost as little as 5% of their bodyweight saw significant reductions.

3. Insulin.

Insulin helps regulate food intake as well as body mass. When insulin levels are higher, it sends a signal that energy is available and to stop eating. Insulin, like leptin, drops when calories are restricted and that sends the opposite signal and promotes food intake.

4. Ghrelin.

Grehlin is a hormone released in the stomach and its primary function is to help regulate hunger by increasing how hungry you are. When you’re in a calorie deficit and losing weight, levels of ghrelin go up. People who are overweight have an additional challenge: When lean people eat a high calorie meal, their ghrelin drops like it’s supposed to. But when overweight people eat a high calorie meal, ghrelin often doesn’t work right and it doesn’t drop, leaving them still hungry.

5. GLP1

GLP-1 is another satiety hormone that is released in the small intestine after you eat. The more weight you lose, the lower your level of GLP-1 and the less full you feel.

6. PYY

PYY is a hormone released from your GI system that make you feel fuller. (It’s a satiety hormone). When you eat, PYY levels go up, which sends a full signal. Research has shown that PYY levels drop after weight loss.

These aren’t the only appetite and energy intake-regulating hormones, but they’re some of the major players.

The idea that “weight loss is all about hormones, not calories” is incorrect. However, it’s true that hormones regulate your body weight and now you can see how. Hormones can influence you to eat more or to eat less and your body adapts to weight loss and calorie restriction by increasing the hormones that make you feel hungrier.

In the end, weight loss always comes full circle to energy balance, but how many calories you eat and how many you burn are heavily influenced by hormones. If you were ever confused about whether weight loss is a matter of calories or hormones, now you know the answer is both.

How To Mitigate Metabolic Adaptation

You now understand what metabolic adaptation is (and isn’t). Mainly, you feel like eating more, and also, your body burns less and you move less.

But the question still remains – what can you do about? How do you fix metabolic adaptation?

Again, the bad news is, you can’t stop metabolic adaptation. These responses are hardwired into your biology, right down to your genes. The good news is, you can mitigate some of the effects with smart nutrition and training strategies. In the Journal of Strength And Conditioning Research review, 7 strategies were listed and confirmed to be scientifically sound.

Most of them revolve around achieving two important goals:

1. Decreasing hunger (or increasing fullness).

2. Minimizing the decrease in energy expenditure.

Don’t expect to see anything novel or “magical” on the list. These solutions are simple concepts that most people are already familiar with. What they often don’t realize is why they work and how important it is to do them consistently.

Even if these strategies seem simplistic, don’t brush them off. Instead ask yourself how many of them you are using and how consistently. If you’re already applying all these strategies, then pat yourself on the back for doing just about everything that you can. There’s nothing else you need to do except to stop worrying about metabolic adaptation.

7 Strategies To Combat Metabolic Adaptation To Weight Loss

1. Don’t lose weight too fast.

It surprises most people when they hear that losing weight faster doesn’t increase your risk of regaining it, because that’s a common belief. But studies show that, at least if slow weight loss is defined as 0.8 pounds to 1.5 pounds per week and fast weight loss is defined as 2.6 to 3.9 pounds per week, then there is no connection between losing faster and weight regain. In fact, it’s likely that quicker early weight loss increases motivation to keep going.

But there are downsides of losing weight too fast. One thing that does correlate with more rapid weight loss is a loss of lean body mass. One study found that people who lost 1.4% of their body weight per week lost more muscle than people who lost only 0.7% per week. It’s also well known that the leaner you are, the higher the risk of losing muscle. So lean people who try to rush it are taking a big risk.

Anything you do whatsoever that triggers a drop in muscle will make the effects of metabolic adaptation worse. Maintaining your LBM is the utmost priority when you’re in a deficit dieting for fat loss.

Heavier people can lose more fat each week than leaner people, but it’s still best to drop weight slow and steady. The rule of thumb has always been to aim for one to two pounds per week or 1% per week maximum.

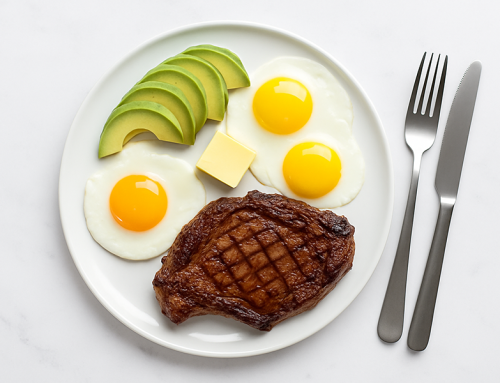

2. Keep your protein intake high.

Want another reason not to lose muscle? Hunger hormones aside, another reason hunger increases when dieting is because muscle loss has occurred. Losing muscle is another signal to increase appetite, which makes sense because losing muscle could be interpreted in the body as a “starvation.”

Out of all three macronutrients, protein is the most important if you’re trying to reduce metabolic adaptation because it helps preserve lean body mass. Protein also has a higher thermic effect, so it helps support continued fat loss.

In addition, protein helps suppress appetite more than any other macronutrient. The hunger hormone ghrelin is not only responsive to food in the stomach, it’s profoundly responsive to specific macronutrients, namely protein. When you include protein with a meal, ghrelin is suppressed more, and you feel fuller longer.

How much protein, exactly? If you look at the science, the recommended range for people resistance training is .73 to 1.0g per pound of body weight per day. The classic rule of thumb for protein intake in the bodybuilding community is 1 gram per pound of bodyweight per day (which matches the upper end of the evidence-based range).

For lean people in an aggressive deficit, there’s a rationale for eating even more protein to help protect lean body mass. Some researchers suggest that the leaner you are and the bigger your deficit, the higher you scale up your protein. This is why some bodybuilders take in even more than 1 gram per pound during contest prep.

Protein prescription can be more nuanced than following the traditional bodybuilder’s rule. If you are overweight or obese and you use 1 gram per pound of bodyweight you’ll overestimate your protein target big time. For this reason, a different formula is needed. We could prescribe the protein by pounds of lean body weight but most people don’t know their lean body mass. A simple formula is 1 gram of protein per pound of goal body weight. Evidence from the scientific literature usually sets the guideline between .55 to .7 grams per pound of bodyweight for people who are overweight.

If you’ve had a hard time hitting protein goals before, do keep in mind that there’s a range for acceptable protein intakes and it’s not that hard to at least hit the low end of the range. On the other hand, if you’re lifting hard, in a deficit, and already lean or dieted down and if you want to optimize your results, it’s usually wise to aim on the higher side than the lower side.

3. Customize carb and fat intake for your own personal preference.

There’s a common belief in the low carb diet world that insulin is a major player in fat gain. Known as the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis of obesity, it says that if you eat carbs, that stimulates insulin and then the insulin promotes the storage of those carbs as fat while keeping existing fat trapped inside the fat cells.

A lot of people who follow low carb diets made their choice for this reason, but the evidence doesn’t support the hypothesis. Low carbohydrate diets can work if you can stick to them, but they don’t work because they control insulin. They work for the same reason every other diet works – a calorie deficit.

Sometimes low carb diets look more effective, as it’s not uncommon to see impressive weight loss right out of the gate. But quick weight loss during the early stages on low carb diets is usually explained by the loss of water and glycogen. Long term weight loss studies show that low carb diets are no more effective than any other diet.

With this in mind, the research today suggests that how many grams of carbs or fat you eat is not as important as most people think. The best approach may be to set your calories, set your protein and then fill in the rest with carbs and fat any way you want. For fat loss, calories and protein are the bigger priorities.

Given this freedom of choice, a lot of people may still opt for lower carb intakes and that’s fine. But thinking about metabolic adaptation, there is a good argument to not get extreme with carb cutting. Not only is leptin highly responsive to carbs, but also there are lines of research showing that thyroid levels drop when carbs get down under around 120g a day or so.

Also, carbs can help support training performance when you’re in a calorie deficit. If your resistance training performance stays 100% with lower carbs, that’s one less thing to worry about. But if your performance drops because cutting carbs killed your energy, then increasing carbs is the better option. Ultimately, your best bet is to set macros based on what you can most easily stick with as well as what supports your performance in the gym the best. Low carb may not be as advantageous as many people think.

4. Focus on fiber

Eating enough fiber is important not only for good health but also for successful weight loss. High fiber diets are consistently associated with better weight loss. On a simple level, high fiber foods require more chewing and eating more slowly is well known to help reduce calorie intake. And because the calorie density is usually low in fibrous foods, it’s a lot harder to overeat them (especially vegetables).

What many people don’t know is that high fiber foods can affect your satiety hormones including GLP-1 and PYY. Those same hormones that decrease due to metabolic adaptation, can be increased by focusing on fiber.

Gastric emptying is also slowed down when you eat meals high in fiber. When food leaves your stomach more slowly that means you feel fuller longer (again, counter-acting one of the effects of metabolic adaptation). One study showed that oatmeal (a high fiber food), lowered the rate of gastric emptying substantially more than corn flakes (a lower fiber food). Carbs are not bad, but choose your carbs wisely. Focus on fiber and carbs that make you feel fuller.

According to the FDA, 25 grams a day is the recommended amount. Some health organizations recommend up te 35 grams a day. The DRI (daily reference intake) is slightly higher at 14 grams per 1000 calories expended per day. (For example, 28 grams at 2000 calories per day or 36 grams at 2600 calories per day).

There’s no upper limit set for fiber because it’s not considered bad for you to take in higher amounts than the standard recommendations. However, it doesn’t look like there are any extra benefits of going beyond 40 to 50 grams a day. Plus, at really high levels of fiber intake, it’s possible to start getting gastrointestinal symptoms that you surely don’t want.

5. Implement the diet break and refeeding strategies

There is nothing terribly wrong with dropping down into a calorie deficit and staying there for the duration of a typical diet phase. This is called continuous energy restriction. But it’s not the only approach, and there may be a better way.

Intermittent energy restriction (not to be confused with intermittent fasting) is where you are in a deficit most of the time (because you want to lose fat), but at strategic intervals you raise your calories out of deficit and up to maintenance level. Diet breaks and refeeds are the two most common ways to do this.

The refeed is not a new technique at all – it’s been around the bodybuilding diet world for years, but only recently has it started to be mentioned in scientific journals. A refeed is where you raise your calories to maintenance (or even slightly higher), usually for one or two days a week. When you take two refeed days, you can either split them up (like three days low and one day high), or take two days in a row (like five days low and two days high).

A diet break is similar because you periodically raise your calories to maintenance level. A significant difference is that you keep your calories higher for a longer period of time. The typical diet break is at least one week long, and preferably two weeks long.

For both refeeds and breaks, you eat the same mostly unprocessed, healthy foods. This is absolutely not to be confused with “cheat” days, you simply eat more of the same nutritious, healthy foods you were during the deficit phase. The difference is, the increase in calories during the higher days comes mostly in the form of carbohydrates. One reason is because we know that leptin is responsive not only to increased calories but specifically to carbohydrate calories. It has been theorized that this could restore this hormone closer to normal, non-dieting levels.

In the past, some people would describe that as “spiking the metabolism.” This may occur, but current evidence suggests that if it happens, it’s not that significant, especially for a one day refeed. Therefore, refeeds probably don’t increase fat loss in the short term. After all, you’re eating more calories. With a longer diet break, there may be some restoration of metabolism-regulating hormones that got zapped from calorie restriction.

But even though scientists are still debating whether refeeds and diet breaks do anything to help hormones and metabolism, a proven benefit of both strategies is helping you to retain your lean body mass when you diet. If you stay in a deficit all the time, the risk of muscle loss is higher. If you raise calories periodically, your chances of maintaining all your hard earned muscle is higher. Maintaining muscle means maintaining your metabolism better.

As I mentioned before, leptin is especially responsive to carbohydrate intake. Furthermore, carbs will increase insulin. Most people in the diet world are conditioned to think insulin is a “bad hormone” (mainly because of low carb diet dogma). But insulin is an anabolic hormone that helps maintain fat free mass. It can also reduce protein breakdown and it stimulates MTOR, which is the signaling pathway for muscle growth.

Many athletes also report improved training performance when they use refeed days. Anything you do that improves your weight training performance is going help you maintain your muscle. That in turn will help maintain your metabolism and mitigate metabolic adaptation.

One more benefit, and it’s a huge one, is that taking refeed days and or diet breaks can increase your adherence to a diet over time. While it may seem like inserting periods of maintenance calories across the duration of a fat loss program would decrease your rate of fat loss, studies have shown the opposite. The MATADOR study showed that a group taking 2 week breaks throughout the diet in the end, finished with the same amount of fat loss as the group that stayed in the deficit the whole time.

It doesn’t seem to make sense on the surface, or you might think for sure, the breaks must have spiked metabolism and maybe they did a little. But the primary explanation is probably that the people who were always in a deficit were suffering more from hunger and deprivation and went off their diet more so they weren’t in as much of a deficit overall as they thought they were. The group taking diet breaks strategically and intentionally achieved the same fat loss but with less discomfort or struggle.

6. Counteract the drop in energy expenditure by increasing your physical activity

By far the biggest component of your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) is your basal metabolic rate (BMR). BMR is all the energy you burn just to maintain normal body functions. That includes the energy needed by your internal organs and brain. This can be as much as 70% of your TDEE. BMR stays fairly stable through life, though it slowly decreases with age if you don’t maintain your lean body mass with resistance training.

Your TDEE also includes an activity component. Exercise activity thermogenesis (EAT) is your formal training like an intense weight lifting session or cardio workout. In most people who are not full-time athletes this adds up to only 5% to 10% of your TDEE. . Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) is all the other activity you do every day, including from housework, yardwork, leisure time activities, and even little unconscious body movements like fidgeting or pacing around the room. NEAT could account for as little as 15% of TDEE if someone is sedentary to as much as 50% in someone highly active.

One of the adaptations to weight loss and dieting is a reduction in NEAT, and it’s often unconscious and imperceptible. Most people simply don’t realize that they move less all day long after they’ve dieted down and lost weight. Most people’s attention is focused on formal workouts and think that ramping up cardio is the way to keep fat loss going or ramp up the rate of fat loss.

If you increase your intentional exercise activity (like doing more cardio), that is indeed one way to offset some of the metabolic adaption. This is why you see the majority of dieters who exercise increase the amount of their exercise over the course of their fat loss phase. This is also why smart fat loss seekers start a cutting phase with a fairly modest amount of cardio, maybe only three or four days a week for a half an hour, and then increase the cardio based on their results. If you start with high volume cardio from day one, you end up doing a ridiculous amount of cardio that is unsustainable or simply not practical.

What most people miss is the power of the NEAT component. When you think about how formal exercise only makes up a small part of your TDEE, it pays to think about increasing NEAT as well. The calories burned from NEAT can add up to far more than you could ever achieve from formal exercise.

Once you become consciously aware that your overall level of daily activity usually drops after you’re dieted down, that alone is enough for most people to make adjustments to counter it. Fitness trackers with step counters can be a big help. While 10,000 steps may be a good goal for many, the best idea is to know your usual baseline and make sure you don’t fall below that number, or ideally, increase it a little bit as you get leaner. Many people set their fitness tracker to vibrate on the hour as a reminder to get up move for 5 minutes before getting back to work.

It’s not worth worrying about the tiny little things that make up NEAT, but it is worth it to start doing things like taking the stairs and not the elevator. Also, adopting a mentality that exercise doesn’t have to come in 30, 40 or 60 minute chunks is helpful. Smaller bouts of “micro exercise” spread out across the day can make a big difference and many people will find this easier than going for the typical 150 minutes a week in 30 minute continuous sessions. Beyond keeping your calorie expenditure up, you can get health benefits from as little as 10 minutes of continuous walking at a brisk pace (around 3mph)

You may realize that when you’re restricting calories you don’t have as much energy. You may feel tired and aren’t very motivated to move. You can overcome that with a little discipline. The main thing to remember is that one of the metabolic adaptations to weight loss is a drop in your activity level throughout the whole day, which may be unconscious, so you don’t notice it. When you’re consciously aware of this, you can make conscious efforts to counteract it – not only with your usual workouts, but also keeping up your walking and other non-exercise activity.

7. Make resistance training with progressive overload the primary focus of your exercise plan.

No strategy is more important than doing progressive overload resistance training, and doing it consistently.

It’s ironic, but most people who are trying to lose weight believe that the ideal type of exercise for reaching their goal is cardio. Cardio training is vital for your health. It also helps increase and maintain weight loss and it does so very well as long as the diet is controlled and you don’t out-eat your exercise.

But cardio alone is not enough. Most types of cardio won’t help you maintain lean body mass. In fact, if you do extreme amounts of cardio, attempting to lose fat faster, it can increase the risk of muscle loss when you are in a calorie deficit.

If you’re trying to reduce metabolic adaptation, you have to maintain your lean body mass. That means resistance training should be your highest exercise priority. When you combine resistance training with an optimal protein intake, those two strategies alone reduce the risk of muscle loss more than anything else you can do.

Standard weight training programs with straight sets usually won’t burn as many calories as steady state cardio, and burning calories is not the main reason we do it. But it does contribute to your exercise activity energy expenditure at the same time it helps you build muscle.

It can be challenging to increase weight training volume over the course of a diet. But as fat loss progresses, increasing the training volume and frequency can sometimes be another option to boost energy expenditure. Plus, there is a direct relationship between resistance training volume and muscle growth, so if you can another day of weight training or increase the sets slightly and still recover from it, that’s yet another strategy you can add to your list.

Conclusion

Always remember that exercise and nutrition programs must be customized. Using a metabolic adaptation protocol is no different. All human bodies operate under the same physiological laws, so the same strategies apply to everyone. To minimize adaptations and optimize results, everyone needs to eat enough protein. Everyone needs to do resistance training. Everyone needs to stay active. However, you have a lot of room to adjust your approach based on your preferences and your lifestyle.

Your choices for training, for example, are endless. Choose a weight training style you like. Choose a type of aerobic exercise you like. Stick to walking if more intense types of cardio don’t suit you. Even when choosing a protein goal, there are recommended ranges, not a single target you must hit. All you have to do is make sure you at least hit the minimums and it’s up to you if you want to aim for the maximums.

Don’t be afraid to experiment – not only with training but also with strategies like refeeds and diet breaks. Even though it may seem like your body is fighting you every step of the way, and you’re cursing that damned metabolic adaptation, keep tweaking and adjusting your approach. Ditch what doesn’t work for you, keep doing more of what’s working, and you will reach your weight loss and fat loss goals.

-Tom Venuto, author of Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle – The Bible Of Fat Loss

Related: Does Building More Muscle Increase Your Metabolism, Burning More Calories Even While You Sleep?

Tom Venuto is a natural bodybuilding and fat loss expert. He is also a recipe creator specializing in fat-burning, muscle-building cooking. Tom is a former competitive bodybuilder and today works as a full-time fitness coach, writer, blogger, and author. In his spare time, he is an avid outdoor enthusiast and backpacker. His book, Burn The Fat, Feed The Muscle is an international bestseller, first as an ebook and now as a hardcover and audiobook. The Body Fat Solution, Tom’s book about emotional eating and long-term weight maintenance, was an Oprah Magazine and Men’s Fitness Magazine pick. Tom is also the founder of Burn The Fat Inner Circle – a fitness support community with over 52,000 members worldwide since 2006. Click here for membership details

Scientific References

Roberts B, Martinez-Gomez M, Metabolic Adaptations to Weight Loss: A Brief Review, Journal of Strength And Conditioning Research March 2021.

Fothergill E et al, Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after The Biggest Loser competition, Obesity, 24(8): 1612–1619, 2016

Martins, C, et al, Metabolic Adaptation is Not a Barrier to Long Term Weight Maintenance, Am J Clin Nutr, 1;112(3):558-565, 2020.

Great stuff thanks! Just bought the BTFFTM book as a thanks!

Thanks for posting!

So happy to be following you again. I was trying another program with a fancy iPhone app and subscription, but it just made me depressed and stressed out. Back to the expert I should have trusted all along! Thank you!

Kristi, thanks for following again. depressed and stressed is no fun.

Tom, I am so grateful I found you, your book, and your site. I am thoroughly enjoying learning how to make lifelong changes. From this blog I think this paragraph really hit home, “When this concept clicks in your mind, you suddenly realize why so many people gain back weight they lost. It’s not easy to eat less than you were used to eating for years and move more than you were used to moving for years. That’s the sobering reality.”

It’s very basic and makes all the sense in the world but not something we talk about often or fully grasp most of the time. Thank you for taking so much time to provide us with a wealth of knowledge. I am just starting out my journey but thank you for being the main encouragement and support for it.

Jennifer, thanks for reading and commenting. This stuff can be hard to grasp at first, but its also the kind of thing that all of a sudden one day it clicks and you totally get it. Then you just have to act on that new understanding. still not easy, but it becomes simpler; no more confusion. Cheers!

Your articles are the best, but this one, in particular, is be so beautifully explained…it’s just an absolute game changer and it has given me so much hope. All of the “sciency” stuff makes perfect sense. Seriously. Thank you for writing this.

Thank you. Keep up the hope… and even build it into belief.

Love your articles Tom.

One thing that I would like to add is your age factor. As you get older, you need to re evaluate your diet. I find that it needs constant “tweaking” ….almost like competing again.

As you body ages and changes, you find that you have to make adjustments to nutrition and your exercises. It is only part of the natural aging process and your own personal genetics.

Bob, for sure age factors into the equation. the good news is, those two strategies – weight training and adequate protein help a TON at overcoming drops in lean mass that otherwise would happen with age (sarcopenia), and the protein is even more important with age too due to anabolic resistance. as we get older we not only have to keep making adjustments to account for the adaptive stuff, but at the same time keep tweaking to account for the aging stuff. (tends to include weight training exercise selection and loads too as the joints usually dont feel quite the same

Wow, this is fascinating reading! I’m going to have to read this a few times to take it all in but it makes complete sense! As a middle aged woman trying to lose only 5kg, this seems to be particularly relevant to me. I love the idea that moving more during the day helps. I work standing up so I move around a lot and I even dance at my desk! I also like to do pushups on the kitchen bench or wallsits while I’m waiting for my lunch to heat up in the microwave. These are only small things, but I like to think they help. I reassess my meal plans each week and I’ve realised I seem to function better with higher fat % than carbs so I’m currently tweaking my food in that direction. I’m sure it will continue to evolve. It really helps having access to your knowledge, Tom, because often the things I feel work best for me are very different to what other fitness and diet people tell us. This post is a case in point! Thank you so much for this article.

Great blog again Tom.

Poppie Pete

Hi Tom!

I read BTFFTM years ago and only partially stuck to it. After having two kids and being a depressed stay at home mom, I decided to read your book again and I didn’t skip the mental training this time! I made a meal plan, cardio and weight training schedule and am having slow but steady success! I recently took a diet break without even realizing it and I was so happy that it talked about it in this article. I’m excited to finally reach my fitness goals! Thanks for everything!

Thank you for posting such an insightful article. For weight loss which is sustainable; nothing works better than a combination of strength training, calorie deficit, nutritious meal and a good sleep.

Great article! It’s helpful to know all the factors of the fat loss equation since sometimes just focusing on on or another isn’t enough. It’s also helpful to know ways we can combat metabolic adaptation!

Hi, love your work and your down to earth science based take on things.

In calorie restriction for life extension contexts there are theories on why the restriction extends the lifespan.

One such theory is that the body switches from replacing damaged cells to repairing them and this “saves” telomer loss as it reduces cell division. I wonder what happens to those replaced cells vs the repaired. If the cell material when cleared out not is reused, to what degree would that contribute to the apparent slowed metabolic rate. What do you think?

Hi Irene. slower metabolic rate with caloric deficit is simply adaptive thermogenesis. The body decreased energy expenditure as an adaptation to conserve energy… life extension by caloric restriction has only been shown in rodents and lower species like yeast, worms and flies. In primates early evidence shows signs of biomarkers of slower aging so it is possible. However, it is still hypothetical whether it extends lifespan in humans and one thing we do know is that you’d have to “starve for life” to get the benefit… if you start in your 50s for example, its too late to make much difference. Also, miserable way to live and its unhealthy to be so underweight. One of the poster boys for caloric restriction weighed like a buck 20 or so… lack of muscle mass when you get older is worse. learn more: https://www.burnthefatinnercircle.com/public/Caloric-Restriction-for-Life-Extension.cfm

Hi, totally agree with your response and it seems like a way of life without living, hellish. However you didn’t answer the question stated.