What are net carbs? And if your goal is fat loss, do they matter? Should you track them if you’re on a fat loss diet with a strict carb limit? Are net carbs even relevant and important, or is it just a marketing ploy for low carb products?

Net Carbs: A Controversial Topic

First of all, “net carbs” is not an official term recognized by the US Food and Drug Administration. Net carbs get the most attention in the low-carb diet world and also among people wanting to manage their blood sugar. Outside of those contexts, the usefulness of the net carb concept is debatable. In fact, macro tracking based on net carbs can lead to big mistakes that slow down fat loss.

But ever since low carb diets got popular, net carbs have worked their way into the broader conversation. Today, even people who aren’t low carbers are asking about net carbs.

To cut to the chase, and summarize my post, I’m making the case that most healthy people would be better off to ignore net carbs, and count all carbs with the usual Atwater factor of 4 calories per gram. That’s what I recommend in all my books and programs, including my newest, The Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle Guide To Flexible Meal Planning For Fat Loss

If you look for answers in the scientific literature, you discover that it’s true your body doesn’t always absorb all the caloric energy that’s locked in food. Some food can pass through your system without being metabolized.

For example, suppose a serving of broccoli has 4 grams of carbs, but 2 grams of it is fiber. If your body can’t absorb those 2 fiber grams, can you legitimately say you only ate 2 grams of carbs, and the other carbs (and calories) don’t count?

Well, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to say that carb calories your body does absorb could be called the “net.” It also might be a fair estimation to count only about half the carbs in fiber and sugar alcohols. But it’s not always that simple, especially when it comes to how the net carb concept is promoted by the industry.

Low carb food products often make claims on the label about what does and doesn’t count. But what’s printed on the label may not accurately reflect the grams of carbs your body really absorbs.

Fortunately, if we stick to what the science says instead of what the low carb industry claims, and if we understand the differences between carbs and how your body processes them, you can make sense of it all.

What Are Net Carbs, Exactly?

Net carbs also go by the name impact carbs or digestible carbs. The term digestible carbs gives you the tip-off about what they are. Net carbs refer to the portion of a carbohydrate food that’s actually digested and absorbed by the body, so your body can use the calories they contain.

There are many kinds of carbs including simple and complex, fibrous or starchy. In naturally-occurring carbs, it’s the ones high in fiber that are most relevant to the net carbs discussion.

What all carb foods have in common is that they’re made of sugars. When it’s a simple carb, there may be only one or two sugars linked together. You find this in foods like fruit (fructose), milk (lactose), and of course, table sugar (sucrose). If it’s a complex carb, there are long chains of sugars linked together. You find these in foods like rice, potatoes and whole grains.

For your body to actually absorb the calories in any carb, they have to be broken down into the individual sugars. In certain types of carb foods, your body can’t break down and absorb those individual sugars and the calories they contain. They go right through your body without being metabolized. The two types you hear about the most are fiber and sugar alcohols.

This is the reason some people say you should subtract fiber from total carbs and the number of grams you’re left with is net carbs. If you’re tracking macros, proponents of net carbs say it’s the net number not the gross number, that you should record.

Fiber and sugar alcohols may be a legitimate deduction, at least part of them, but for reasons I’ll explain in a minute, I usually tell most healthy people not to bother.

And in the case of the low carb diet food industry, I hang a big “buyer beware” sign. The net carbs and impact carbs idea is being used to manipulate you into buying low carb products and making you feel good about doing it.

How Fibers Are Different

Fiber is a carb, but it’s not digested the same as other types of carbs. When fiber comes from a natural whole food source, the fiber doesn’t get absorbed in the small intestine. Due to its molecular structure, fiber can’t be broken apart into individual sugar units by the digestive enzymes. The intact fiber travels right through to your colon.

What happens once fiber gets there depends on what type of fiber it is. If the fiber is insoluble, that means it doesn’t dissolve in water. This is why it helps prevent constipation. It also passes through the colon without providing any caloric value and it doesn’t affect blood sugar or insulin. This is one of the reasons eating enough fiber helps achieve good health.

Soluble fiber on the other hand, dissolves in water. It gels in the digestive system and that slows down the passing of food. It can also help make you feel fuller. This is one of the reasons eating adequate amounts of fiber helps with weight control.

The difference as it pertains to net carbs is that when soluble fiber reaches your colon, the resident bacteria ferment the fiber into short-chain fatty acids (SCFA). These SCFAs provide some caloric energy. Each gram of soluble fiber has 1 to 2 calories, depending on the type.

Although there are usable calories in this type of fiber, it doesn’t have much effect on blood sugar levels and may even help reduce it. This is another reason why we hear so much about fiber being healthy.

Do Net Carbs Matter?

Okay, you now know how carbs and fiber are processed in the body and you know what net carbs are. That brings us to the practical questions: If your goal is fat loss, do net carbs really matter? Should you count them? What if you’re on a low carb diet? Are net carbs even relevant?

To answer, it’s important to realize that this whole idea of net carbs, including subtracting fiber from the carb count, has been advanced by low carb diet companies. It has been embraced primarily by low carb dieters with weight loss goals and by some people concerned with blood sugar.

Worrying about net carbs and subtracting fiber really isn’t even a conversation that needs to take place with everyone else who is metabolically healthy and eats a balanced macro diet (like Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle).

Subtracting fiber from whole foods and then aiming for a total net carb goal for the day makes little difference to your results one way or the other. If you get taken in by low carb industry advertising and use net carbs to track your macros, you might even end up eating more calories than you think you are.

Why Are Net Carbs Are Promoted So Much?

If net carbs aren’t that important, then why does this subject continue getting so much attention? In a word: money. Low carb dieting is no longer a novel idea or small diet niche. It has gotten so mainstream, a lucrative industry of low carb programs, supplements, drinks and food products has blossomed.

Two different market research firms published reports in 2020 saying that the ketogenic diet business alone – which is only one segment of the low carb industry – is projected to reach 18 billion a year in sales by 2026.

Net carbs and impact carbs are not scientific terms. It’s the low carb industry that promotes the concept and uses the terms on their product labels. They do this as a way to make their foods look lower in carbs than they really are. By making them fit the parameters of their diets, they boost sales.

Picture a low carber scanning the store shelves for low carb foods or protein bars and seeing the grams of carbs on the label. If there’s even a hint that the carbs are too high, the consumer might say to himself, “That’s way too many carbs,” and then not purchase the product.

On the other hand, if the carbs are advertised as really low, it looks like a free pass. It looks guilt-free, at least in a low-carber’s mind, and that’s an easy sale.

Regardless of what macros we choose for our diet – high carb or low carb – either way, we should be eating mostly unrefined whole food. But this low carb food marketing trick has people eating piles of processed candy bars, cookies, brownies, muffins, chips and other snacks that are disguised as healthy or at least appearing to fit into the rules of low carb dieting.

The most unfortunate result of this kind of marketing is that millions of people are focusing on the wrong C for weight loss – carbs, instead of calories. Low in carbs doesn’t necessarily mean low in calories, especially when we’re talking about so-called “keto-friendly” diet products.

Not only are many of these loaded with fat (at 9 calories per gram), there may still be metabolizable calories in the carb sources used. These include sugar alcohols, glycerin, and isomaltooligosaccharides (IMOs).

Sugar Alcohols

Sugar alcohols are sugar-free (no sucrose) sweeteners. Chemically speaking, the molecule is similar to sugar, as the name implies. They also have similarities to alcohol, also as the name implies, but they don’t contain any ethanol. Common sugar alcohols include erythritol, sorbitol, mannitol, maltitol, lactitol, and xylitol.

Sugar alcohols have fewer calories than regular sugar, but they’re not calorie free, with about 1.5 to 3.0 calories per gram. Regular sugar has 4 calories per gram. Most sugar alcohols, while lower in calories than regular sugar, do contain carbs and they do get absorbed. The research confirmed this many years ago. A 1990 study said:

“Sugar alcohols reaching the colon were almost completely digested. Because the experimental conditions of this study mimicked the usual way of consumption of the three sugar alcohols, little calorie saving can be expected from the chronic consumption of these sugar alcohols in so-called sugar-free products.”

Erythritol is an exception, which is why we took a closer look at it in a previous blog post. Virtually none of the calories in erythritol are absorbed.

Despite the fact that there are metabolizable calories in most sugar alcohols, some low carb companies still insist they shouldn’t be counted in the carb grams on the label. They justify this claim by saying that sugar alcohols don’t affect insulin or blood sugar response as much. That’s a benefit many low carb dieters are looking for, but blood sugar management is a health issue, not a weight control issue per se.

Glycerin / Glycerol

Another carb source that low carb companies claim you can exclude is glycerin (sometimes spelled glycerine), or glycerol. This is a syrupy liquid about 75% as sweet as sucrose. It’s used as a sweetener, it helps retain moisture, and in frozen products, helps to prevent ice crystals from forming. And yes, it has calories – about 4.3 calories per gram – that can all be absorbed. Many nutrition bars have more than 9 g of glycerin in a single-serving bar.

The FDA says glycerin is safe as a food additive, but the FDA certainly does not say the carbs or calories don’t count. According to the FDA, the synthetic glycerin must be included in the grams of total carbs on the nutrition facts panel. Some low carb food companies include it in the total carb count on the back nutrition label, but on the front, they exclude it as a non-impact carb. Yep, they made up that term too.

For example, one company’s “low carb” chocolate peanut butter meal bar contains 23 grams of total carbohydrates, but the front of the box says it has “only 3 g of net carbs.” The fiber and glycerin have been subtracted even though they include metabolizable carbs and calories.

Isomalto-oligosaccharides (IMOs)

Food label shenanigans have been going on for a long time, but over the years, the sweeteners and other ingredients used have changed. Years ago, it was just fiber and sugar alcohols. Today, the net carb discussion also involves another ingredient found in low carb nutrition bars: isomalto-oligosaccharides (IMOs).

On the labels, IMOs may be called a “100% natural prebiotic fiber.” Not only is this considered another deductible, lowering the net carb count, it sounds healthy too, doesn’t it? But while IMOs may occur naturally in some foods, the types used in low carb nutrition products are processed.

That’s not all. The science says that IMOs are “digestible and caloric.” A protein bar label might say, “only 3 grams of net carbs” because they subtracted 17 grams of sugar alcohols and or IMOs, but the truth is, that bar has 20 grams of total carbs and those carbs have calories. Studies on IMO metabolism show that they have at least 2 calories per gram. In addition, studies show they impact blood sugar.

There’s one popular protein bar brand which uses large amounts of IMOs in their products. You can see the type of IMO in the ingredients list, and the huge fiber count on the label. If you were subtracting all of those grams from the total carb count and thinking the calories didn’t count either, well, oops.

IMO Health Claims

Some diet food companies are not only implying that IMOs are “non-impact” carbs that don’t count, they’re also making health claims. After all, fortifying a food with fiber seems like a healthy thing, right?

In a recent report on dietary fibers published by the FDA, IMO’s were not even on the list as a fiber. One of the companies that produces IMOs for the nutrition bar industry petitioned the FDA to have IMOs added. Their request was denied. Here was the FDA’s response:

“Based on our consideration of the scientific evidence and other information submitted with the petition, we conclude that the strength of the evidence does not show that consumption of IMO has a physiological effect beneficial to human health. Consequently, we do not plan to propose to amend the list of nondigestible carbohydrates that meet the definition of dietary fiber to include IMO as a dietary fiber based on this scientific evidence.”

The problem remaining is, this response from the FDA is not a law that prevents claiming IMOs don’t count, so it looks like the label loophole is still there. This means many consumers will continue being fooled into believing a number of false things:

- These carbs don’t count.

- These carbs don’t have calories that can be absorbed.

- This is a fiber similar to what you’d get in whole foods like veggies or grains.

- This fiber has special health benefits.

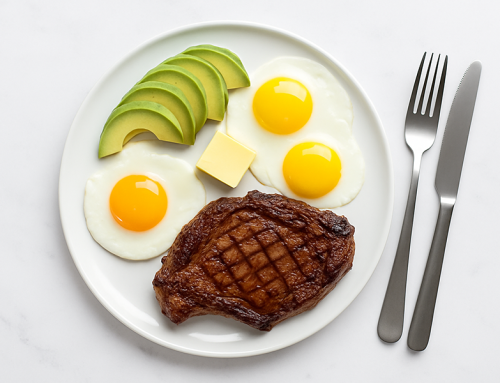

I’m not saying you have to give up protein bars, if you enjoy them, any more than you have to give up any food you can fit into your macros in moderation. I don’t believe in or promote the idea of completely banning any macro or any individual food. But I also know these packaged snack foods don’t carry the nutritional value of an omelet and fruit, or chicken and vegetables just because they have 20 grams of protein and 15 grams of fiber.

That protein and fiber count may look like a health food by the numbers, but it’s still a processed food. And depending on the type of fiber, it may or may not hep with blood sugar control.

Fiber: A Legitimate Deduction, But Not Much Impact

There’s controversy over the carbs in sugar alcohols, glycerin, and IMOs. But you could argue that at least a portion of the fiber in whole foods is a legitimate deduction because it’s not fully absorbed by your body.

In the scientific journal Diabetes Spectrum, licensed dietician Janine Freeman explained:

Dietary fiber is not digested and absorbed in the small intestine like glucose. Fiber is fermented in the large intestine to produce fatty acids, which are then absorbed and used as energy. Foods rich in hemicellulose and pectin (generally known as soluble fiber), such as fruits and vegetables, are more completely fermentable than foods rich in celluloses (insoluble fiber), such as cereals. Although the energy derived from fermented fiber varies among individuals, the estimated energy yield from fiber is between 1.5 and 2.5 kcal/g…

Although fiber does contribute to calories, its effect on blood glucose is likely minimal. For individuals with diabetes who desire this level of detail, practitioners may suggest subtracting the total grams of dietary fiber from the grams of total carbohydrate on the Nutrition Facts panel. But the effect is probably insignificant if the amount of dietary fiber is less than 5 g.

In another study, published in the Journal of Nutrition, when the Atwater factor of 4 calories per gram of carbohydrate was used, and a diet with 2800 calories and 37 grams of fiber was analyzed for net energy, the metabolizable energy was overestimated by only 4.6 to 6%.

Most people erroneously say there are zero absorbable calories in fiber, but as these studies indicate, some types of fiber contain energy that’s partially absorbed. These include seeds, whole wheat bread, peanut butter, bananas, and other foods that are partially digested by the bacteria in the large intestines.

So should you subtract the fiber from your carb count when you track macros and make meal plans or not? You can if you want to. But it’s not likely to make much difference. Also, looking at the metabolizable energy value of fiber, sugar alcohols, and IMOs, it’s more accurate to say they all have somewhere around 2 calories per gram, not zero. Even then, you have to be careful not to fall for marketing scams that trick you into thinking you’re compliant on carbs, but meanwhile, increasing your calories.

A downside of tracking net carbs in any way is that it will make meal planning and macro calculations more of a headache. Who wants more number counting and crunching? I’m a huge advocate of macro-based meal planning, but the way I feel about this today, I think the less calorie and macro math you have to do, and the easier you make your meal planning and macro tracking, the better. Plus, given the complexity of human digestion and metabolism, there’s no way to know for certain exactly how many carb calories are really absorbed.

Here’s another way to look at it: The American Dietetic Association recommends 20 to 35 grams of fiber a day and the FDA’s recommends 25 grams or 11.5 grams per 1000 calories of energy expenditure. Even if you were on a high fiber diet by ADA or FDA standards, and even if you absorbed none of the energy, this would be a maximum margin of error of only about 100 calories or so, which isn’t enough to have much effect.

If anything, this type of “error” in calculations would work in favor of fat loss, because you’d erring on the side of lower carbs and lower calories. If some of the caloric energy in fiber is not absorbed, it means you’re taking in fewer calories than you think, not more. With this line of logic, if you stick mostly with whole foods and simply aim to eat enough naturally occurring fiber, then not tracking net carbs helps with fat loss.

If a food product label subtracts large amounts of sugar alcohols, glyerin, and IMOs, the net carbs may look extremely low, and if you’re focused only on carbs, and not at all on calories, you may be eating more than you think. If a nutrition bar boasts “only 2 grams of net carbs” on the label, then even though it might have 300 calories, it almost makes a low carb dieter feel like they can eat as much as they want. If you eat those processed foods often or in large amounts, and especially if you’re on a tight calorie budget, then your focus on net carbs and not calories works against you, not for you.

Plus, if you were being fooled by the low carb industry into buying processed and packaged foods based on net carb label claims, you might eat less nutritious foods compared to if you were focused on eating more veggies and other whole foods that don’t have labels and aren’t processed. Let’s be honest: Is eating low carb cookies and chocolate peanut butter protein bars all day long really practicing good nutrition? There’s no substitute for a diet consisting of mostly unprocessed whole foods.

Also remember, almost all dieters under-estimate how many calories they eat unless they’re tracking their intake. They also over-estimate their calories burned from exercise. So if you eat a high-fiber diet, from unprocessed whole foods, that would leave you consuming a bit less than you thought, and would help offset some of the places you over-estimated. That’s why it would only be a positive thing for fat loss.

Keep Your Meal Planning And Macro Tracking Simple

Creating meal plans based on calories and macros is worth the effort, and in my opinion, almost essential when you’re first starting out and you want to learn about nutrition and how it impacts body composition. But there’s no need to complicate your macro setup more than you have to.

I simply use the calories and macros exactly as they appear on the label or in the nutrient data base. If I have a cup of broccoli for example, that’s about 25 calories, 2 g of protein and 4 g of carbs, with 2 g of fiber. On my meal plan spreadsheet, I use 25 calories, 2 g of protein and 4 g of carbs, just like the label says.

In my original Burn The Fat, Feed the Muscle book, as well as in my newest book, The Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle Guide To Flexible Meal Planning For Fat Loss, we make no use of “net carbs” or any related terms, nor do we suggest you subtract fiber. We simply recommend the following:

- Aim to eat in a calorie deficit for fat loss (15% to 30% under maintenance is typical).

- Eat plenty of high fiber foods, mostly from whole food sources.

- Track your macros as long as it’s helpful, if not, follow habit-based eating guidelines, portion or plating systems, and use intuitive and mindful eating.

- Eat unprocessed foods most of the time (80%-90% of your calories).

- Get into a feedback loop where you adjust calories (and macros) according to your actual weekly results, not by theoretical calculations.

So now you know the answer to the question, what are net carbs. It boils down to this:

Even if the “net carbs” or “impact carbs” concept is accurate as in the case of natural fiber and even if it’s helpful in certain situations, such as for diabetes, let the buyer beware, because many label claims are misleading. These terms are more low carb marketing gimmick than anything.

Also, for what it’s worth, not only are “net carbs” and “impact carbs” unscientific and not recognized by the FDA, there have in fact, been class action lawsuits. There are petitions now for the FDA to start evaluating these label claims more closely.

Tom Venuto,

Founder, Burn the Fat Inner Circle

Author, Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle

PS. My newest e-book, The Burn the Fat, Feed The Muscle Guide to Flexible Meal Planning For Fat Loss was just released this week and is currently available for instant download. To learn more about “Flexible Macro-Based Meal Planning” CLICK HERE.

Tom Venuto is a natural bodybuilding and fat loss expert. He is also a recipe creator specializing in fat-burning, muscle-building cooking. Tom is a former competitive bodybuilder and today works as a full-time fitness coach, writer, blogger, and author. In his spare time, he is an avid outdoor enthusiast and backpacker. His book, Burn The Fat, Feed The Muscle is an international bestseller, first as an ebook and now as a hardcover and audiobook. The Body Fat Solution, Tom’s book about emotional eating and long-term weight maintenance, was an Oprah Magazine and Men’s Fitness Magazine pick. Tom is also the founder of Burn The Fat Inner Circle – a fitness support community with over 52,000 members worldwide since 2006. Click here for membership details

Scientific References:

Baer DJ, et al. Dietary fiber decreases the metabolizable energy content and nutrient digestibility of mixed diets fed to humans. J Nutr. 127(4). 579-586, 1997.

Beaugerie L, et al. Digestion and absorption in the human intestine of three sugar alcohols. Gastroenterology. 1990 Sep;99(3):717-23.

Freeman, Janine RD, LD, CDE and Charlotte Hayes, MMSc, MS, RD, LD, CDE, Low-Carbohydrate- Food Facts and Fallacies, Diabetes Spectrum 2004 Jul; 17(3): 137-140

Gourineni V, Gastrointestinal Tolerance and Glycemic Response of Isomaltooligosaccharides in Healthy Adults, Nutrients. 2018 Mar; 10(3): 301.

Howarth NC, et al, Dietary fiber and weight regulation, Nutr Rev, 59(5):129-39, 2001.

Kokmoto T et al, Metabolism of (13)C-Isomaltooligosaccharides in Healthy Men, Biosci Biotechnol Biochem, 56(6):937-40, 1992.

Lattimer J, Haub M, Effects of dietary fiber and its components on metabolic health, Nutrients, 2(12):1266-89. 2010.

Miles, CW et al, Effect of dietary fiber on the metabolizable energy of human diets. J. Nutr. 118(9). 1075-1081. 1988.

Miles CW. J, The metabolizable energy of diets differing in dietary fat and fiber measured in humans. Nutr. 122(2):306-11. 1992.

Mithieux, G, et al, Intestinal glucose metabolism revisited, Res Clin Pract, 105(3):295-301, 2014.

Oku T, et al, Evaluation of the relative available energy of several dietary fiber preparations using breath hydrogen evolution in healthy humans, J Nutr Sci Vitaminol, 60(4):246-54, 2014.

Roberfroid M, Caloric Value of Inulin and Oligofructose, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 129, Issue 7, July 1999, Pages 1436S–1437S, 1999.

Turner, N et al, dietary fiber. Adv Nutr., 2(2): 151–152, 2012.

Weickert, M et al, Metabolic effects of dietary fiber consumption and prevention of diabetes, Nutr,138(3):439-42. 2008.

Wisker E, Metabolizable energy of diets low or high in dietary fiber from fruits and vegetables when consumed by humans. J Nutr. 120(11):1331-7. 1990.

Wheeler, M et al, Carbohydrate issues: type and amount, J Am Diet Assoc, Am Diet Assoc

108(4 Suppl 1):S34-9, 2008.

Zou M, Accuracy of the Atwater factors and related food energy conversion factors with low-fat, high-fiber diets when energy intake is reduced spontaneously. Am J Clin Nutr. 86(6). pp 1649-1656, 2007.

Leave A Comment